Abstract

A critical phase of scenario making is the choosing of scenarios. In the worst case, a futures researcher creates scenarios according to his/her subjective views and cannot see the real quality of the study material. Oversimplification is a typical example of this kind of bias. In this study, an attempt towards a more data sensitive method was made using Finnish transport policy as an example. A disaggregative Delphi method as opposed to traditional consensual Delphi was applied. The article summarises eight Delphi pitfalls and gives an example how to avoid them. A tworounded disaggregative Delphi was conducted, the panelists being representatives of interest groups in the traffic sector. Panelists were shown the past development of three correlating key variables in Finland in 1970– 1996: GDP, road traffic volume and the carbon dioxide emissions from road traffic. The panelists were invited to give estimates of their organisation to the probable and the preferable futures of the key variables for 1997 – 2025. They were also asked to give qualitative and quantitative arguments of why and the policy instruments of how their image of the future would occur. The first round data were collected by a fairly open questionnaire and the second round data by a fairly structured interview. The responses of the quantitative three key variables were grouped in a disaggregative way by cluster analysis. The clusters were complemented with respective qualitative arguments in order to form wider scenarios. This offers a relevance to decision-making not afforded by a nonsystematic approach. Of course, there are some problems of cluster analysis used in this way: The interviews revealed that quantitatively similar future images produced by the panelists occasionally had different kind of qualitative background theory. Also, cluster analysis cannot ultimately decide the number of scenarios, being a choice of the researcher. Cluster analysis makes the choice well argued, however.

Need for systematic scenario formation

One critical question concerning scenario formation is how to form scenarios relevant to decision-makers? How to make sure that the scenarios are not only futurist’s prejudices or his/ her own subjective ideas of the policy options? What are the relevant ranges of the values of the variables between scenarios?

The aim of this paper is to illustrate that one way to tackle this problem is to use the Delphi method applied in a disaggregative way. ‘Disaggregative’ here means that the goal of consensus is not adopted but the responses are grouped to several clusters by using cluster analysis as a systematic tool for grouping the core quantitative variables. The rather bareboned clusters are then complemented with the respondent’s qualitative arguments in order to construct more holistic scenarios. In this study, Delphi panelists are representatives of interest groups instead of individual professionals because the approach is considered an intermediate between expert poll and committee work in policy formation. The approach also raises some new problems, which are further discussed. The methodology is illustrated by the Delphi data gathered of the transport policy of Finland for 2025.

Case: Finnish transport policy

The disaggregative Delphi application of this study focuses on the future of the volume of economic output, traffic and environment. The problematique was reduced to three key variables:

- the gross domestic product measured in market exchange rates (GDPmer) in real terms

- the road traffic volume measured in vehicle kilometers

- the carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions of road traffic measured in metric tonnes

A decoupling of GDP and road traffic volume would imply immaterialisation or nonmaterial economic growth in more traditional vocabulary. The decoupling of road traffic volume and the CO2 emissions of road traffic would imply dematerialisation, or more simply, technical development of vehicles. In spite of all the writing about technical development, dematerialisation, decarbonisation and a qualitative change in the economy, the three key variables correlated strongly in 1970 – 1996 in Finland, especially from 1978 to 1996 [1– 3] (Fig. 1).

The purpose of the application was to produce alternative scenarios focusing on these key variables for 1997 – 2025, which would be relevant from the point of view of the interest of transport and environmental policy. The Delphi panel consisted of fourteen interest groups

Avoiding Delphi pitfalls by disaggregation

To produce future scenarios for the economy, transport and environment an application of the Delphi method of two rounds was used. The idea of the traditional Delphi was to get an expert panel estimation of probable future on a topic that has many interpretations and is hard to formalise in mathematical models. It may also be used when there is insufficient data on the topic or when changes in the relations between variables are intuitively expected [4– 9].

Especially the many interpretations and an expected change in the relations of the key variables are at present in the case of carbon dioxide policy of traffic sector. Programmes and discussions about it are conducted at many levels and organisations worldwide in UN [10], OECD Environmentally Sustainable Transport (EST) project [11], EU, US and Japan. In connection to EU traffic policy, the Ministry of Transport and Communications of Finland also organised a Working Group of CO2 Emissions [12].

The Delphi method is an iterative process consisting of at least two rounds (sometimes even five). The purpose of the multiple rounds is to give panelists feedback from the previous rounds where experts make arguments and/or evaluations for some issues to happen. The argumentative rounds are usually anonymous, so that the status or background organisation of the experts would not affect others’ opinions. The ideal of the procedure is that the panelists would make some tacit knowledge explicit and that the best argument should win. Another ideal of the traditional Delphi was to reach a consensus among the panelists [4,7,9].

As the readers of this journal probably remember, the traditional Delphi method was subjected to severe criticism in the mid-1970s. Several alternatives to Delphi were promoted, such as Shang inquiry by Ford [13], POSTURE by Brockhaus [14] and SPRITE by Bedford [15]. Also, Hill and Fowles [16] wrote critically about Delphi in the special issue of Technological Foresight and Social Change (TFSC). Even the pro-Delphi scholars like Turoff [17] and Linstone [18] were concerned about the many pitfalls of the traditional Delphi.

Another wave of criticism can be found from the pages of TFSC in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Benarie [19] discussed the philosophical limitations of Delphi and Delphi-like methods. Woudenberg [20] and Kastein et al. [21] criticised poor reliability and accuracy of Delphi forecasts in comparison to other methods. Rowe et al. [22] observed inadequacies in the actual questions and feedback of Delphi applications. Webler et al. [23] were especially worried about panelists’ lack of commitment to the process and developed Delphi towards a committee work. As the first wave of Delphi critique more or less totally questioned the worth of Delphi, the second wave merely promoted modifications for better study design.

However, Delphi survived the two waves of criticism as can be seen in the extensive bibliography of Gupta and Clarke [24]. The following text summarizes eight Delphi pitfalls from the critical discussion and explains how the pitfalls were dealt with in this study.

Biased selection of the panelists

Delphi critique often remarks that in applications little effort is put to a reliable selection of the panelists [15,16,18]. Often used conomination tends to result in a biased sample, because experts apparently conominate colleagues that represent similar school of thought. Cuhls [25] has suggested that conomination is a good start, but certain basic background factors, such as sex, age and professional background, should be checked before the Delphi manager can safely stop looking for new panelists. She also suggests scanning of publications, institutions and public databases relevant on the study object to get reliable samples. For example, the panel of a recent Delphi study ‘‘The Future of Mobility’’ consisted of 96% of men, only 14% of under 40-year-old experts and 51% of technically or economically educated experts [26].

In this study, the panelists were selected in a somewhat unusual way. Instead of individual experts, the participants were fourteen interest groups that have an interest to the transport and environmental policy in Finland. The rationale behind this choice is that the disaggregative Delphi serves as an alternative to committee work in forming normative policies but aims not at replacing policy makers with scientists. The organisations represented the following categories:

Traffic administration

- Ministry of Transport and Communications

- Rail Administration

- Road Administration

Environmental administration

- Ministry of the Environment

Local administration

- Helsinki Metropolitan Area Council/Transportation Department (manager’s own view)

Lobbying groups of different traffic modes

- Bus Transport Federation (bus transport)

- Automobile and Touring Club of Finland (passenger cars)

- Traffic League (surface public transport and soft modes)

- Traffic Policy Association Majority (soft modes)

Other groups with economic interest

- The Confederation of Finnish Industry and Employers (interest in freight transport)

- Finnish Road Association (road construction)

- Transport Workers’ Federation (trade union, e.g., road haulage drivers and and bus drivers)

Environmental group

- Dodo—The Living Nature of the Future (a group of young students)

Ministry of Treasury, the car import organisation and an older environmental group Finnish Nature Conservation Federation dropped out in the first round because of lack of time and/or feeling that their views would be presented by some of the other panelists. Water and air transport related interest groups were not involved, because for geographical reasons they do not compete much with road traffic in Finland. The lack of an air transport interest group can be considered a bias, however.

Disregarding organisations

Anonymity is usually maintained among Delphi panelists in order to bring out more honest views without having to be afraid to lose face or a job. On the other hand, individuality and anonymity have been claimed to be reasons for the lack of commitment consequently resulting in high dropout rates, scarce written arguments and hasty ‘‘snapjudgments’’ instead of cautious ponder and analysis of the issue [15,23]. One solution worth a try could be to ask panelists to act as representatives of their organisations instead of as individual experts. The author has not seen references suggesting this. In this study, organisational representation was experimented with, mainly because the application was designed to improve the process of typical committee work where participants do represent their organisations.

The representatives of the organisations were sampled systematically by making a phone call to the operational top managers of the organisations. After that, the organisation was free to work in its own way to appoint a representative or representatives. Some managers participated themselves whereas some delegated the task to their subordinates, who were phone-called as well. Three organisations appointed two representatives and some of the other respondents may have asked their colleagues or bosses for second opinion. The representatives of three other organisations changed between the rounds, one because of lack of personal familiarity to quantitative approach, one because of retirement and one because of change of employer. The change of opinion of these three organisations between the rounds was not different from the other organisations. The respondents were asked for their organisation’s view on the most probable and the most preferable future. This is in line with the Policy Delphi applications [7,17,27].

Focusing on the organisations instead of individuals brought out interesting features. Some representatives protested that their organisation did not have official quantitative statements on the carbon dioxide emissions of road traffic or GDP. They were explained that no official declaration was asked for, merely well argued estimates and evaluations. This sufficed for most participants but two managers admitted only to represent their own views instead of the organisation’s. Some respondents complained that their own view differs from what they regarded as the organisation’s view. In these cases, the organisation’s view was asked for anyway.

It was not the focus of the study to analyse the average opinion of an organisation. It might differ significantly from the organisation’s opinion, because organisation is something else than just a sum of its individuals. There seemed to be discrimination in the selected organisations, since only 2 women as opposed to 12 men were gathered by this method.

Forgetting disagreements

Applications of Delphi have been criticised of ignoring and not exploring disagreements, which could generate artificial consensus [4,15 – 17]. In this study, a goal of consensus between the participants was not adopted. Instead, a set of alternative long-term traffic and environmental policy scenarios were produced. This type of unconsensual, or disaggregative, Delphi has been applied already in the 1970s [28,29]. Also, consensus seemed to be rather unimportant goal in the big national technology foresight studies conducted by Delphi in the 1990s [30] (the conclusion is less clear in Ref. [31]). Arguments for a more disaggregative Delphi have been stated by other Delphi users as well [27,32]. However, most of the articles of the Delphi book of Adler and Ziglio [33] still seemed to have a consensus approach.

Ambiguous questionnaires

Delphi literature is full of warnings and descriptions of poorly formed questionnaires (e.g., Refs. [7,9,15,22,34]). The actual questions have been especially criticised for being too abstract and leaving room for too many interpretations. In the first Delphi round the study material was gathered with a questionnaire that included a figure of the development

of GDP, road traffic volume and CO2 emissions from road traffic in 1970 – 1996 inFinland. The panelists were asked to manually draw the trends for the most probable future and the most preferable future for 1997 – 2025. The questionnaire was pretested with and commented by four traffic professionals (see Ref. [34]).

Oversimplified structured inquiry

Another pitfall in Delphi applications is oversimplified structured inquiry that does not leave room for new ideas [16,18,30]. To avoid this, the panelists were asked to write down arguments in an open form why and how they expected the most preferable future to happen and why they believed the most probable future would happen. The most preferable future was defined as a future that is technically possible and desirable taken into account all the aspects and impacts relevant for the organisational viewpoint. The definition was a tryout to help the panelists separate themselves from too conservative or pessimistic views (‘‘daily realism’’) concerning social change without sliding to total science fiction. The definition was unfortunately ambiguous, one interpretation covering only direct utility of the organisation and another enabling a more altruistic approach as well. Another requirement was that the answers should form a coherent scenario instead of isolating the three variables from each other or from their economic, social and ecological context.

Feedback reports without analysis

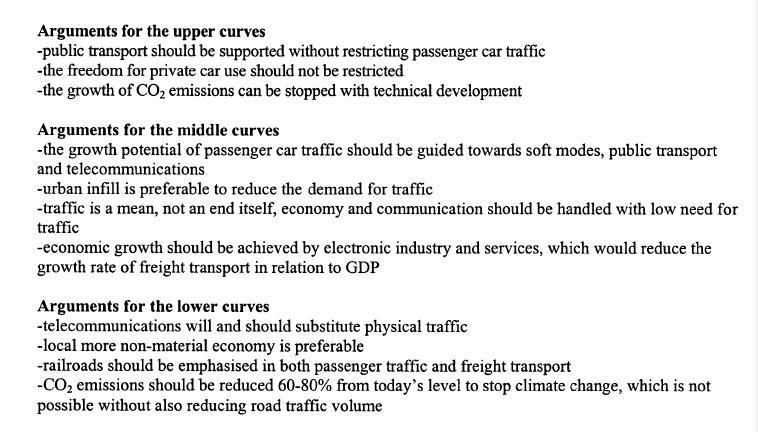

Scarce feedback and summary reports are another criticised feature of Delphi studies [15,18,30,34]. Thus, a summary report was produced that presented all the responses of the three variables separately and included the arguments produced by the open form. Every respondent could see his/her own organisation’s first round answer emphasised with a different colour in relation to other responses, which is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Forgetting the arguments

Although the fundamental ideal of Delphi is that the best argument should win, in actual applications arguments have not had a central role [17,30,35]. To get more in-depth arguments, the second Delphi round in this study was conducted by interviews. Because the open questionnaire of the first round produced less material than was hoped, a more structured thematic interview was conducted in the second round.2 The interviewee was systematically asked to comment on the arguments presented by estimations of lower and upper curves than their own responses. The respondents were encouraged to give arguments supporting their view and allowed to change their answers from the first round on the basis of the arguments of the other respondents. This is a similar feature to the ‘‘Argument Delphi’’ developed by Kuusi [30], originating partially from argumentation rules of van Eemeren et al. [38].

The role of the Delphi moderator was to state contra-arguments in order to get more in-depth arguments from the respondents. This approach immediately leads to doubts of bias originating from the explicit and implicit ways in which the contra-arguments are presented by the interviewer. Four ways to ameliorate this effect were employed: (a) in the beginning of the interviews, it was made clear that the method includes presenting other panelists’ contra-arguments; (b) the interviewer tried to isolate himself from the arguments by expressions such as ‘‘often a contra-argument is stated to the point you are making that.. .’’; (c) in the earlier interviews, the interviewer presented also hypothetical contra-arguments on the basis of literature and 8 years experience in the transport field; (d) in the later interviews, the cumulative total chain of arguments and contra-arguments presented to a certain issue was dealt with. The interviews lasted from 1.25 to 4 h and the total tape-recorded material was approximately 35 h.

Fig. 2. Illustration of round one results to a particular organisation x concerning preferable estimates of road traffic volume of Finland. (The apparent erroneous way to present the volume scale with five numbers originates from the first round questionnaire and was deliberately repeated in the second round, because the choice of scale might have had influence on the second round responses.)

The methodological concern to make the interviews rational well-argued discussions seemed to be successful. A lot in-depth arguments were produced, such as reference to specific research or statistics and revelation of the social theory of mobility behind the answer, etc. These are difficult to get with a questionnaire or an interview without contra-arguments. The interview strategy adopted in this study has features of ethnographic decision-tree modeling, although here decisions were not computerised to a yes/no dichotomy (see Ref. [39]).

As a rule, exploratory thematic interviews should be made first and then, based from the interview, form a more exact questionnaire for the next round(s).3 This would clarify concepts, improve the relevance of the questionnaire and increase motivation to participate. There were three reasons to break the rule in this study. First, the starting point of the study, i.e., the three curves in Fig. 1, was so illustrative, that respondents were (correctly) expected to be motivated to answer. Second, the respondents had a high motivation because they worked directly with the issues. Third, why conduct argumentative interviews if there are no process borne arguments nor statements to argue about?

Lack of theory

Delphi users have often been criticised for the lack of theoretical understanding of the methodological procedure and less often for the lack of theoretical framing of the substance [16,35,41]. The harshest conclusion has probably been stated by Bell [41]:

So far, Delphi researchers use, create, test or know precious little—if any—social theory. (p. 270)

This critique seems overly harsh. Especially the philosophical and theoretical foundations of the Delphi procedure have been considered quite often. To mention a few Scheele [42]made an effort to place Delphi in the context of phenomenological epistemology; Mitroff and Turoff [43] presented five philosophical inquiry systems and stated that Delphi has a role to play in all of them, but the applications might be different from each other; Rowe et al. [22]placed Delphi in the context of judgment and decision-making theories (in business administration); Kuusi [30] developed a ‘‘general theory of consistency’’ as a philosophical framework and analysed how Grupp has tested certain theories of technological paradigms. There are also obvious connections of Delphi to Habermasian ‘‘undistorted communication’’ and critical pragmatist planning theory, but they are impossible to analyse in detail here (see, e.g., Refs. [44,45]).

Actual testing of social theories with Delphi applications is not as common. In this study, the responses were interpreted in the light of theories of environmental policy, but the analysis will be made in a separate paper. Although the critique of lack of theory is overestimated, it still is a relevant pitfall to keep in mind.

The features of the traditional Delphi and the disaggregative Delphi are summarised in Table 1. The table includes also some extra features of this study that are different from the traditional Delphi.

[1] K.Mäkelä, Suomen liikenteen hiilidioksidipäästo¨ t.The website of Technical Research Centre Finland, http://www.vtt.fi/yki/yki6/liisa/co2dats.htm, 1997. [The Carbon Dioxide Emissions from Traffic in Finland.]

[2] R.A. Finn, Koko maan liikennesuorite autolajeittain vuosina 1970-1997/2020E. The website of Finnish Road Administration. Avilable at: http://www.tieh.fi/aikas/liiks.htm, 1997. [Road traffic volume by mode in the whole country in 1970 – 1997/2020 (forecast).]

[3] Statistics Finland: Volyymi-ideksit 1860 – 1995. The website of Statistics Finland, http://www.stat.fi/tk/to/sarjat.html, 1997. [Volume indexes 1860 – 1995 (of GDP of Finland).]

[4] H.A. Linstone, M. Turoff (Eds.), The Delphi Method. Techniques and Applications, Addison-Wesley Publishing, Don Mills, 1975 (620 pp.).

[5] W.E. Riggs, The Delphi technique. An experimental evaluation, Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 23 (1983) 89– 94.

[6] G. Rowe, G. Wright, F. Bolger, Delphi: A reevaluation of research and theory, Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 39 (1991) 235 – 251.

[7] E. Ziglio, The Delphi method and its contribution to decision-making, in: M. Adler, E. Ziglio (Eds.), Gazing into the Oracle. The Delphi Method and its Application to Social Policy and Public Health, Jessica Kingsley Publishers, London, 1996, pp. 3– 33.

[8] A. Rotondi, D. Gustafson, Theoretical, methodological and practical issues arising out of the Delphi method, in: M. Adler, E. Ziglio (Eds.), Gazing into the Oracle. The Delphi Method and its Application to Social Policy and Public Health, Jessica Kingsley Publishers, London, 1996, pp. 34 – 55.

[9] M. Mannermaa, Tulevaisuuden hallinta-skenaariot strategiatyo¨ skentelyssa¨, Ekonomia-sarja, Suomen Ekonomiliitto and WSOY, Porvoo, 1999, 227 pp. [Management of future—Scenarios in strategic management, in Finnish.]

[10] IPCC: Climate change 1995. Impacts, adaptations and mitigation of climate change: Scientific – technical analyses, in: R.T. Watson, M.C. Zinyowera, R.H. Moss, D.J. Dokken (Eds.), Contribution of Working Group II to the Second Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Cambridge Univ. Press, New York, 1996 (879 pp.).

[11] OECD: Environmentally sustainable transport. Final Report on Phase II of the OECD EST Project. Volume 1 Synthesis Report. Environment Directorate, Environment Policy Committee, Working Party of Pollution Prevention and Control, Working Group on Transport, ENV/EPOC/PPC/T(97)1/ FINAL, 81789, available at http://www.oecd.org/est, 1997.

[12] Ministry of Transport and Communications: Toimenpiteet tieliikenteen hiilidioksidipa¨a¨sto¨ jen va¨henta¨miseksi, Publications of the Ministry of Transport and Communications 16/99, Edita, Helsinki, 1999, 80 pp. [Measures to decrease carbon dioxide emissions of road traffic—Publication of the working group of CO2 emissions, in Finnish, Abstract in English.]

[13] D.A. Ford, Shang inquiry as an alternative to Delphi: Some experimental findings, Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 7 (1975) 139 – 164.

[14] W.L. Brockhaus, A quantitative analytical methodology for judgmental and policy decisions, Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 7 (1975) 127 – 137.

[15] H. Sackman, Delphi Critique. Expert Opinion, Forecasting, and Group Process, The Rand Corporation, Lexington Books, Lexington, MA, 1975 (142 pp.).

[16] K.Q. Hill, J. Fowles, The methodological worth of the Delphi forecasting technique, Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 7 (1975) 179 – 192. [17] M. Turoff, The policy Delphi, in: H.A. Linstone, M. Turoff (Eds.), The Delphi Method. Techniques and Applications, Addison-Wesley Publishing, Don Mills, 1975, pp. 84 – 101.

[18] H.A. Linstone, Eight basic pitfalls: A checklist in the Delphi method, in: H.A. Linstone, M. Turoff (Eds.), Techniques and Applications, Addison-Wesley Publishing, Don Mills, 1975, pp. 573 – 586.

[19] M. Benarie, Delphi-and Delphi-like approaches with special regard to environmental standard setting, Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 33 (1988) 149 – 158.

[20] F. Woundenberg, An evaluation of Delphi, Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 40 (1991) 131 – 150.

[21] M.R. Kastein, M. Jacobs, R. van der Hell, K. Luttik, F.W.M.M. Touw-Otten, Delphi, the issue of reliability: A qualitative Delphi study in primary health care in the Netherlands, Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 44 (1993) 315 – 323.

[22] G. Rowe, G. Wright, F. Bolger, Delphi: A reevaluation of research and theory, Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 39 (1991) 235 – 251.

[23] T. Webler, D. Levine, H. Rakel, O. Renn, A novel approach to reducing uncertainty: The group Delphi, Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 39 (1991) 253 – 263.

[24] U.G. Gupta, R.E. Clarke, Theory and applications of the Delphi technique: A bibliography (1975 – 1994), Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 53 (1996) 185 – 211.

[25] K. Cuhls, Reasons for a new foresight approach—The FUTUR process in Germany, Paper presented at the conference The Quest for the Futures: a Methodology Seminar, Organised by the World Futures Studies Federation (WFSF) and Finland Futures Research Centre, Turku, Finland, June, 2000, 18 pp.

[26] F. Karmasin, H. Karmasin, Delphi-Studie ‘‘Zukunft der Mobilita¨t,’’ Bericht, Institut fu¨r Motivforschung (ifm), Archiv-Nummer: 5249, available at http://www.oeamtc.at/aka_publ, 1999, 74pp. [The website includes also English version but it was not downloadable when the manuscript was written.]

[27] M. Turoff, S.R. Hiltz, Computer-based Delphi processes, in: M. Adler, E. Ziglio (Eds.), Gazing into the Oracle. The Delphi Method and its Application to Social Policy and Public Health, Jessica Kingsley Publishers, London, 1996, pp. 56 – 85.

[28] B. Schwarz, U. Svedin, B. Wittrock, Methods in Futures Studies. Problems and Applications, Westview Press, Boulder, CO, 1982 (175 pp.).

[29] J.F. Preble, Public sector use of the Delphi technique, Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 23 (1983) 75 – 88.

[30] O. Kuusi, Expertise in the future use of generic technologies. Epistemic and methodological Considerations concerning Delphi studies, Acta Universitatis Oeconomicae Helsingiensis A-159, Doctorate Dissertation, Helsinki School of Economics and Business Administration, HeSE Print, 1999, 268 pp.

[31] K. Blindt, K. Cuhls, H. Grupp, Current foresight activities in central Europe, Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 60 (1999) 15 – 35.

[32] M. Wilenius, J. Tirkkonen, Climate in the making: Using Delphi for Finnish climate policy, Futures 29 (9) (1997) 845 – 862.

[33] M. Adler, E. Ziglio (Eds.), Gazing into the Oracle. The Delphi Method and its Application to Social Policy and Public Health, Jessica Kingsley Publishers, London, 1996 (252 pp.).

[34] P.G. Goldschmidt, Scientific inquiry or political critique? Remarks on Delphi assessment, expert opinion, forecasting and group process by H. Sackman, Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 7 (1975) 195 – 213.

[35] S.D. Scheele, Consumerism comes to Delphi: Comments on Delphi assessment, expert opinion, forecasting, and group process by H. Sackman, Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 7 (1975) 215 – 219.

[36] R.K. Merton, P. Kendall, The focused interview, Am. J. Sociol. 51 (1946) 541 – 557.

[37] R.K. Merton, The focussed interview and focus groups. Continuities and discontinuities, Public Opin. Q. 51 (1987) 550 – 566.

[38] F.H. van Eemeren, R. Grootendorst, F. Snoeck Henkemans, Fundamentals of Argumentation Theory. A Handbook of Historical Backgrounds and Contemporary Developments, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, Mahwah, NJ, 1996 (424 pp.).

[39] C.H. Gladwin, Ethnographic decision tree modeling, Qualitative Research Methods Series 19, Sage Publications, Newbury Park, 1989 (96 pp).

[40] S. Hirsja¨rvi, H. Hurme, Tutkimushaastattelu. Teemahaastattelun teoria ja ka¨yta¨nto¨ , Helsinki University Press, 2000, 213 pp. [Research Interview. The Theory and Practise of Thematic Interview, in Finnish.]

[41] W. Bell, Foundations of Futures Studies: Human Science for a New Era vol. 1, Transaction Publishers, New Brunswick, 1997 (365 pp.).

Kategoriat:artikkeli, Artikkelit

Jätä kommentti