Hannu Linturi © Metodix Ltd (published 12.3.2024)

The Institute for Finnish Domestic Languages traces the term ”hybrid” back to biology, where ”a hybrid refers to the crossbreed of two different species, whether it concerns an animal (e.g., mule) or a plant.” In common language, ”hybrid” has spread in many other contexts as well. In the automotive industry, the term refers to a mixture of different types of power: a hybrid car has both a combustion and an electric motor. Both metaphors are suitable for modern Delphi. The method is used just as much quantitatively as qualitatively, in the present as well as in the future, in research as well as in practical development. The actual hybrid leap in development is, however, happening through the acceleration of generative artificial intelligence. Delphi will increasingly gain their momentum from artificial intelligence.

Delphi already have all the elements of a hybrid. It is recognized and acknowledged as a scientific method, but it is also used as a tool for pragmatic organizational development and decision-making. What makes it a hybrid is also its relationship with time. A significant part of the method’s usage is focused on the future, but even then it serves the needs of the present. It is beneficial to identify development alternatives, so that wise choices can be made in the present. From the standpoint of knowledge and to some extent also of science, the future is problematic because one cannot have certain knowledge about it. In this particular sense, all future knowledge is inherently hybrid, diverse, and intermingling. This does not make ”future knowledge” worthless, but it distinguishes it as its own area of knowledge. Mikhail Bakhtin illustrates the difference by categorizing knowledge into three types: scientific, artistic, and existential knowledge.

Scientific knowledge is verified truth, limited by the atomistic nature of knowledge. Such knowledge can be verified with new observations. However, empirical observations do not bend from the absolute truth into a story that would reveal motives and aspirations, conflicts and moments of happiness. According to Bakhtin, that is the task of artistic knowledge, which holds significance even when no detail of the narrative is scientifically true. We recognize the narrative power of ”The Unknown Soldier.” It is a truth understood by many about the Winter War. Bakhtin’s third, existential type of knowledge is the most surprising. It concerns what is not yet but could be. It is thus future knowledge, the most crystallized form of which Pentti Malaska calls vision knowledge. It may be as powerfully monological as Elon Musk’s or polyphonic as in scenario planning. Common to both is that thinking is guided by a strong foundation of unfulfilled ideas, making the presentation coherent and visionary. If the reader or listener accepts the logic of such ideas, they can themselves deduce the future. Musk’s vision of electric cars no longer feels very radical. Regarding space travel, there are more skeptics, but maybe not in twenty years, if our circumstances on Earth deteriorate.

If the key features of modern Delphi were to be condensed into a slogan, it would gain support for the description that the core of Delphi is the argumentation of anonymous experts. According to a recent expert panel (see the Hunch panel https://www.edelphi.org/hunch ), such ”AAE movement” will remain strong in the future, but adaptations to the environment will occur in the methods used. Future developments will strengthen the hybrid features of the method. This is evident, for example, in that many future Delphi (dissensus) will gain popularity over single-future Delphi (consensus). In the processes of multiple futures, the ”artistic” facilitation by the manager (the ”dramaturgy” of Delphi rounds) becomes more significant, which can also be considered a hybrid feature.

Method experts highlight three strengthening hybrid perspectives, whose impact on method development over the next ten years will be significant. The majority of panelists predict that Delphi will increasingly converge and combine with other methods. Weak signals, systems thinking, and scenarios receive the most mentions, with which the connection is already strong even now.

At times, the first round of Delphi is conducted as personal interviews. Interviews are expected to increase as technology facilitates documentation through the automation of speech transcription. Especially in development projects, online and face-to-face activities, as well as online-offline operations, are combined in a manner that allows for the integration of multiple objectives and brings the process closer to decisions and implementations. It is likely that technological development will lead to the improvement of online services to better support both multimethod approaches and diverse work formats.

Delphi’s hybridity is reflected in the fact that its purposes and approaches vary. Anita Rubin (2014) describes four different approaches to futures studies: anticipatory, cultural or interpretive, critical, and analytical approaches. The anticipatory approach is best suited for scenarios where the focus is on a future not too far from the present and influenced by not too many variables. Anticipatory methods are based primarily on time series and mathematical modeling, but other methods can also be utilized. The ultimate goal is to formulate one as clear and precise forecast as possible to aid decision-making and strategic planning.

The cultural approach is based on the view that the future is made up of different alternatives. In building these alternative futures, the values, traditions, and cultural practices of different parties are considered as equally as possible. The most important aspect is not the making of forecasts but the vision, and thus truth is always relative. The methods are mostly hermeneutic, developed on the basis of an understanding approach to science, and they are used to explore, for example, goal setting or the effects of various cultural or social factors on decision-making and, consequently, on the future that materializes.

In the critical approach, the emphasis is not so much on creating forecasts or scenarios per se, but the goal is to question and examine the assumptions and premises from which the future is envisioned. The most important aspect is then the participation and activation of people in social action. On the other hand, the critical approach’s main justification is not just to act as a counter-reaction to the previous two approaches, but the special methods developed within its realm (e.g., Storytelling or Causal Layered Analysis) are seen to have their own significance especially when examining groups, cultures, or practices that are difficult to understand through more traditional perspectives.

The basis of analytical futures studies, in addition to a normative perspective, includes instrumental thinking: ”… futures studies aim to identify possible, probable, conditionally possible, desirable, and frightening alternative futures and then develop tools to shape the future and direct one’s actions over the longer term.” (Rubin 2014) In fact, most of the futures studies conducted, for example, in Finland, and the theories, methods, and models developed within this field can be attributed to analytical futures studies. For example, the theoretical framework used as the basis for this article has been formed from the perspective of analytical futures studies.

All the approaches described by Rubin have been and are used in Delphi. The general expert assessment is that both the cultural and analytical research attitudes will strengthen over the next ten years. However, the critical approach may emerge as the strongest riser, especially if the programmatic collaboration between Delphi and CLA methods is successful. It is important to try to identify also the surprising or disruptive future from the vague future, so that we could timely reinforce the desired and resist the undesired future.

Generative Artificial Intelligence

Human beings are layered with the entire biological evolution up to this point, the last layer being the convoluted cerebral cortex. However, the human genome does not significantly differentiate us from other organisms. We still share a quarter of our genes with the dandelion. Only a few percent of our shared stock of about twenty thousand genes branch us from the chimpanzee. Metaphorically speaking, every person has within them a horse, a snake, and primordial slime. In the Jungian ”mind’s abyss,” conscious understanding is like the cream on the surface of freshly milked milk. Beneath it lie the preconscious and the unconscious, into which personal and species-specific cellars layer. Underneath the ground floor’s floorboards surge the deep currents connecting all living things. The cultural human has emancipated from many of the restrictions of earlier life forms, but the connection has not been severed, even though our dependence on DNA information control has been reducing throughout human history.

Thought and meme travel from brain to brain quickly compared to mutations and gene alterations that occur in generational rhythms. At historical turning points, beliefs can be overturned in months or even weeks. The Ukraine war turned Finnish attitudes towards NATO between two polling measurements. The speed of cultural evolution is insufficient when information starts to be exchanged, transferred, duplicated, and modified outside the brain through artificial intelligence. As before, at such a watershed in human development, dramatic alternatives branch off. If the transhuman critical transition occurs, there is no turning back.

The third information revolution is accelerated by generative artificial intelligence. Here, the organization of information into language-based knowledge and actions increasingly occurs without the human body or interpersonal interaction affecting it. The Hunch panel recognized the significance of the exosomatic flow of information but could not yet fit it into their ten-year future mandate. However, a scenario is visible where exosomatic information processing becomes independent and completely detached from human information processing control.

The ”wild card” in future Delphi panels is artificial intelligence. Or should we use the term support intelligence, as Osmo Kuusi has suggested? The term might be more apt for artificial intelligence at this stage of development, where external intelligence is still defined and subjugated to human goals. Metaphorically, it could be thought that artificial intelligence, for the time being, is still doing the work of a slave for humans. Panels have already incorporated ”brainless” experts with computational capabilities vastly exceeding that of the entire panel combined. The first experiments and experiences of using AI panelists are now under evaluation by the scientific community. It is under investigation how useful, reliable, and ethical the interpretations of information by artificial intelligence are. Through experiments and research, the picture is quickly clarified. The positive significance of artificial intelligence is indisputable, at least in processing information for the production of quick analyses and classifications, which can be circulated during Delphi rounds for use in the discussions and formation of views by the panelists.

Despite artificial intelligence, the primary significance of Delphi remains in the formation of communal knowledge and learning. Even when subjugated, the impact of artificial intelligence is significant. It introduces a new multi-capable resource to community activity. The trend of joint action has been growing for a long time. It has reshaped the workplace and is also affecting education. Increasingly, it is realized that the ultimate learning subject for work and civic life is not the individual but instead the team, community, organization, or even the nation. In addition to brain-to-brain learning, we have (r)evolutionary processes where learning and knowledge formation occur partly or entirely outside of human brains.

I have divided artificial intelligence experiments according to the phases of Delphi into three groups. Language model-based AIs like ChatGPT are already a significant sparring aid for the Delphi manager as they delve into the phenomenon under study, typically structuring, specifying, and delimiting the research subject. Artificial intelligence is used in the initial phase – that is, before the Delphi rounds are conducted – for describing the phenomenon and system analysis, which in turn assists in thematizing the questions. It is useful to utilize AI conversations to help formulate questions and especially future assertions. Generative artificial intelligence, customized with bots, is an effective tool for classifying the expert and stakeholder parties of the panel.

The panel, consisting of experts, has been supplemented in experiments with one or more AI panelists. A characteristic of Delphi is that a group of experts with a comprehensive range of expertises and competencies regarding the phenomenon under examination is assembled. Not all interests and competencies can be included, as the current and future situations are not identical. New factors unknown at the present time may emerge in the future situation, but changes may also occur in the relationships between old factors. Thus, some interests systematically get bypassed when they do not have representation in the present time. An interesting question arises: can an AI panelist simulate such ”silent” parties, thereby making the method more expressive in that sense? Examples of silent parties could be an unborn child or an expert who becomes unemployed due to artificial intelligence in a few years.

A second model for supplementing the panel involves personalized AI panelists, who are well known by the AI but have poor availability in real situations. The Future Committee of the Parliament has “communicated” with both Elon Musk and Greta Thunberg with the assistance of ChatGPT. Kari Hintikka has tested in his doctoral research using the eDelphi software how a Delphi manager can formulate an AI panelist to supplement the human panel based on what gaps remain in the panel’s composition. Conversely, AI can also be used to evaluate how well a selected panel covers the necessary expertise. Hintikka’s experiments introduce several other panelist parameters related to the AI panelist’s characteristics and participation.

In Hintikka’s AI panelist-experimenting Delphi panel, it is considered whether it is meaningful to use historical personalities for future studies. My preliminary stance is that history offers personalities who have a wealth of data online and still have much to offer. It is not primarily about the factual knowledge they held but rather the content and consistency of their thinking and views, as well as the recognition of mechanisms and motives of phenomena. In human action, as in the dynamics of nature, there is much that is variably repetitive and contextualized. It is not so much about sameness as understanding similarity. The current moment is always narrowly tied to the moment of observation, and into this, an era-probing artificial intelligence – with or without personality – can bring significant breadth.

Contrary to the ”data collection” phase in traditional survey research, in Delphi, it is an active and interactive process. During the survey round, the researcher-manager has the right to facilitate – but not manipulate – the panel and panelists’ activities. Their tasks include motivating and informing the panel to participate, for example, by informing participants about the process’s progress, data accumulation, and contents. Part of the activation may increasingly be based on AI algorithms in the future, for example, through data visualization or comment prompts.

Some experiments have already progressed to implementation. xDelphi software (www.xdelphi.ai) has integrated some qualitative ChatGPT services. These include data argument summaries, listing of main points, and sentiment analysis. Also under testing are the description of missing arguments from the data and drafting questions for the next round. An interesting issue to investigate is how AI-assisted Delphi could incorporate fact-checking abilities and, for instance, assessment of data integrity. Delphi has faced criticism over the years regarding the reliability of research techniques, i.e., validity and reliability, and artificial intelligence might be a means to improve both. The third phase tasks of artificial intelligence relate not only to improving research reliability but also to data analyses and reporting results. Analysis is also needed during data collection as we move from one Delphi round to another.

The AI-assisted Delphi process is not just a technical question. One open, fundamental question is whether the AI panelist can engage in dialogue without biasing the process and, if so, by what means? Can the AI panelist listen, or does someone else, such as the facilitator, ”listen” on their behalf? And how much and in what ways can the AI panelist participate in commenting? Hintikka has investigated – with the help of artificial intelligence – how AI-produced ”comments can facilitate deepening, expanding, and enriching the discussion. Value-added comments can manifest in many ways”:

- New perspectives: The comment presents a new and interesting perspective on the topic at hand that has not yet emerged in the discussion.

- Bringing knowledge or facts: The comment contains new information, facts, or research findings that complement the previous discussion and help deepen understanding of the subject.

- Expansion and concretization: The comment expands on previously presented ideas and makes them more concrete or practical.

- Highlighting contradictions: The comment highlights contradictions or challenges that provoke discussion and encourage participants to consider the complexity of the subject.

- Encouragement and support: The comment offers encouragement or support for other participants’ ideas and perspectives, creating a positive atmosphere for discussion.

- Deepening and reflection: The comment takes the discussion deeper and offers reasoned reflections or analyses of the subject.

- Questions and reflection: The comment includes questions that prompt participants to think more deeply about different aspects of the topic or their own views.

- Politeness and interaction: The comment fosters polite and interactive discussion, encouraging participants to share their opinions openly.

In the Delphi experiment, Hintikka has used as a criterion for the use of artificial intelligence that ChatGPT selects the comments that provide the most added value for the panel. Besides producing content or arguments, the AI panelist can be assigned other tasks such as sharing information (summary, contradiction, emotional content, conclusion, etc.) and promoting participation from other panelists (encouragement, further development, clarifying questions, etc.).

In the initial experiments, the premise has been to create an AI panelist as similar as possible to human panelists. Another experimental direction is to identify differences and consider the potential benefits they may bring. Understanding the operation of human panels requires recognizing that human choices are influenced by both communal and individual interests, attitudes, and temperaments. These are all features that artificial intelligence does not ”naturally” possess but must be specifically built into its profile. What if the absence of these features makes AI participation valuable?

Experiences are still being sought on how artificial intelligence stretches into processes whose outcomes are unknown, when the information used by the AI is entirely historical. In long processes such as future barometers, the potential of artificial intelligence presumably increases as data accumulates. Examples of such Delphi implementations include two projects by the National Agency for Education, one exploring the Future of Learning towards 2030 and the other the Future of Skills towards 2035. Both artificial intelligence and expertise have their limitations, recognizing which is important. Artificial intelligence can argue and recognize arguments, but it cannot, at least not yet, think. Expertise requires thinking ability, but it may sometimes be very narrowly defined.

The qualitative goal of the Delphi method is to explore the relevant argumentation for and against different options concerning the development of the phenomenon under study. An argument can be broken down into three main components: claim, justification, and background assumptions (context). In Delphi, the claim is given, but the for-or-against stance is defined by the panelist. What is being tested is the extent to which the AI assistant can pick and categorize different justifications, and what background assumptions each justification requires. For example, take the claim that Russia will not use nuclear weapons, even if the war in Ukraine leads to Russia’s defeat. The claim can be justified by the fact that a nuclear war cannot be won because it leads to mutual destruction. The background assumption then is that decision-making is rational risk assessment by all parties, calculating the benefits and costs of action based on information. However, there are other orientations and sources of identity in humans. Game theories are now trying to consider the so-called Madman phenomenon as well. A madman can perform irrational actions, and that fear can also be used rationally. Absolute belief systems can lead to extreme actions in the fight for ”good,” or they may just be a form of intimidation.

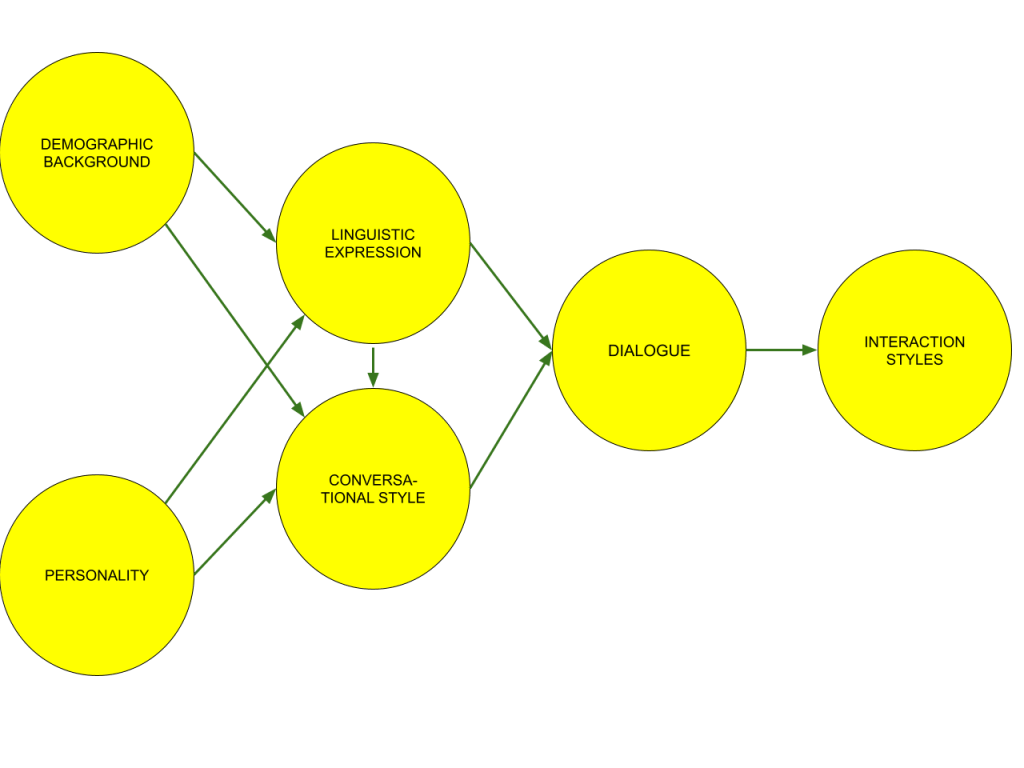

In addition to argument analysis, Delphi may increasingly explore the various background assumptions behind viewpoint differences in the future. Artificial intelligence will have a use in this task. Regulation of artificial intelligence is currently under consideration. Preparatory discussions have addressed not only the rights and duties of people and companies but also what rights and responsibilities are given to artificial intelligence. Perhaps in the near future, the first employment contract between a human and an intelligent machine will be made. The next diagram outlines the essential stages of the Delphi process, with each stage having slightly different relevant AI operations.

The diagram’s circle and phases were constructed by chatting with a bot. The MP-Delphi bot can model the phenomenon, visualize it, and version the model. Evaluation points on how much the AI bots are estimated to help with research have been marked on the inner circles of the diagram.

Common to all research is careful planning and accordingly reliable results. Delphis have their own peculiarities such as the centrality of the panel and questions, but the method’s main distinctiveness lies in the blue and red areas. In Delphi, gathering information is not enough; instead, the goal is to form new understanding within the process itself, produced by a diverse group of experts spurred by active facilitation. The facilitator increasingly has at their disposal an expanding toolkit aided by artificial intelligence.

In the planning phase, there is a low threshold for using generative artificial intelligence. It is advisable to make AI a conversational assistant, with which one can leisurely build a plan that radiates structure and a coherent path both to the process and to the analysis and reporting. The subject of research and development is always a phenomenon that we want to explore and understand. The more structured the phenomenon can be described, the easier it is to set the research goals and questions and identify the phenomenon’s essential themes, influential factors, and questions. The phenomenon also determines who its experts and stakeholders are, i.e., who forms the panel. In all preparatory activities, AI bots can provide significant help. The danger is settling for too quick and simple bot responses.

Facilitation communicates, directs, and inspires the mutual interaction among panelists. Knowledge formation proceeds iteratively, round by round, in a manner that requires the Delphi manager to have analytical abilities for the data’s process phase. The primary task of facilitation is to midwife the participation of the panelists in examining the phenomenon and accelerate the learning dialogue with other panelists. The input for facilitation comes from data accumulated both from the panelists’ external and quantitatively described activity (participation log, voting results) and from internal and qualitatively evaluated outputs such as comments, arguments, and dialogues. A structured background variable available for use is the grouping of the panel, which allows for comparisons and the identification of tensions. Successful facilitation is evident in increased participation, interaction, and argumentation.

Quantitative triggers are generated algorithmically and in real-time as voting diagrams, trend fans of time series, or participation maps mirrored against the panel structure. In qualitative imaging, language model AI techniques will bring entirely new features to the Delphi process shortly. An AI bot can be put to work mining hot discussion themes, arguments, and emotional contents. Identifying different role clusters (near-far) and discussion states (traffic lights) enables new reflection rounds as part of Delphi’s deep-oriented CLA-type iteration.

Technical accelerators for facilitation, participation, and interaction are especially speech interfaces and automatic language versions. With them, multilingual and international panels are increasing. In addition to the manager-facilitator, panelists will be able to produce documentation of their own activity in relation to other panelists in the future.

Reports, studies, and articles follow the same norms as usual. In Delphi, results can also be implementation and decision proposals. In some cases, the result may even be changed activity, as when Delphi is part of an action research process similar to Soft Systems Methodology (SSM). There is a Soft Systems Practitioner bot in ChatGPT that supports system-methodological organizational development. Generative artificial intelligence is particularly good at integrating Delphi with other methods.

The concept of the Futures Wheel (Futures Wheel, Futures Wheel Magician bot) is simple. The phenomenon under consideration is marked in the center of the wheel. The immediate effects of the phenomenon are depicted on the wheel’s first circle. Consequences of each effect are depicted on the second circle. Often, effects and consequences are followed to three circles. The counterpart of the Futures Wheel is the Relevance Tree method. The effects and consequences of the Relevance Tree branch out like branches from the trunk of a tree. Causal Layered Analysis (CLA), developed by Sohail Inayatullah, fits well into Delphi iteration where not only is each round iterated, but also layers to deeper meanings and interpretations. The most important and common associated method is scenario planning, in the construction of which language-based AI is partly displacing the currently commonly used future matrix method. Or perhaps a more precise description would be that AI will assist in creating the matrix.

Delphi is a versatile method. Variables that distinguish different Delphi variations include the process’s goal (consensus vs. dissensus), task (action such as decision vs. knowledge), time (present vs. future), and context (research, organizational or community development, pedagogy). It is expected that AI aids will be developed quite quickly for different variations. The task of research is to create new knowledge, understanding, and insights about different phenomena and processes. The main function of new knowledge and understanding is to advance society’s, i.e., everyone’s, common development. Artificial intelligence shares some features with social media earlier. It is a big promise of democracy but also a tool to polarize and cause chaos. The multivocal process nature of Delphi means that it is remarkably difficult to misuse.

Literature

- Ahvenharju, Sanna (2022) Futures Consciousness as a Human Anticipatory Capacity – Definition and Measurement. Turun yliopisto. PDF Full Text https://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-951-29-8892-1 .

- Airaksinen Tiina, Halinen Irmeli, Linturi Hannu (2016) Futuribles of Learning 2030 – Delphi supports the reform of the core curricula in Finland. European Journal of Futures Research. Special topic: Education 2030 and beyond. Internet https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40309-016-0096-y.

- Bell, Wendell (1997, 2003) Foundations of futures studies, Vol I-II, New Brunswick: Transaction Books.

- The Delphi Technique: Past, present and future prospects. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, Volume 78, Issue 9, Pages 1487-1720 (November 2011)

- Dimitrow, Maarit (2016) Development and Validation of a Drug-Related Problem Risk Assessment Tool for Use by Practical Nurses Working with Community-Dwelling Aged. Helsingin yliopisto, farmasian tiedekunta. Helsinki. Verkossa https://helda.helsinki.fi/handle/10138/167914

- Gordon, T.J. (1994) The Delphi Method. Futures Rsearch Methoodology. Millennium Project.

- Gordon, T.J. (2008) The Real-Time Delphi Method. The Millennium Project. Futures Research Methodology – V3.0. Verkossa http://www.millennium-project.org/FRMv3_0/05-Real-Time_Delphi.pdf .

- Kakkuri-Knuuttila, Marja-Liisa (2001) Mitä on tutkimus? Argumentti, väittely ja retoriikka. Metodix.

- Kauppi, Antti ja Linturi, Hannu (2018) Kansalaisfoorumin viisi tulevaisuutta. Internetissä https://metodix.fi/2018/11/30/kansalaisfoorumin-viisi-tulevaisuutta/ .

- Korhonen-Yrjänheikki, Kati (2011) Future of the Finnish Engineering Education – A Collaborative Stakeholder Approach. ISBN 978-852-5633-48-1. TEK. Miktor. Helsinki. Verkossa http://www.tek.fi/ci/pdf/julkaisut/KKY_dissertation_web.pdf.

- Koskimäki Teemu (2022) Expert perspectives on achieving global sustainability with targeted transformational change. A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University. PDF-julkaisu https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/bitstream/1885/274587/1/TK%20-%20PhD%20thesis%20-%20Revised%20version%202022%20FINAL.pdf .

- Kuusi, Osmo (2000) Delfoi-metodi. Internetissä https://metodix.fi/2014/05/19/kuusi-delfoi-metodi/ .

- Kuusi, Osmo (1999) Expertise in the Future Use of Generic Technologies. Epistemic and Methodological Considerations Concerning Delphi Studies. Interneissä http://bit.ly/3ayzN4e .

- Laakso, K., Rubin, A. & Linturi, H. 2010. Delphi Method Analysis: The Role of Regulation in the Mobile Operator Business in Finland. Phuket, Thailand: PICMET 2010: Technology Management for Global Economic Growth. 18.- 22.7.2010, 2698-2704.

- Laukkanen, Minttu (2020) Sustainable business models for advancing system-level sustainability. Acta Universitatis Lappeenrantaensis -tutkimussarja 889. ISBN 978-952-335-470-8 ja ISSN 1456-4491. LUTPub-tietokanta www.urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-335-471-5 .

- Linturi, Hannu & Rubin, Anita (2011) Toinen koulu, toinen maailma. Oppimisen tulevaisuus 2030. Turun yliopiston Tulevaisuuden tutkimuskeskus. Tutu-julkaisu 1/2011.

- Linturi, Hannu, Rubin, Anita, Airaksinen, Tiina (2012) Lukion tulevaisuus 2030 – Toinen koulu, toinen maailma. Otavan Opiston Osuuskunta. 978-952-6605-00-5 (pdf), ISSN-L 2242-1297, ISSN 2242-1297.

- Linturi, Hannu, Linturi, Jenni ja Rubin Anita (2013) eDelphi – metodievoluutiota verkossa. Metodix https://metodix.fi/2014/11/26/edelfoi-metodievoluutiota-verkossa/ .

- Linturi, Hannu, Rubin Anita (2014) Metodi, metafora ja tulevaisuuskartta. Futura 2/2014.

- Linturi, Hannu (2007) Delfoin metamorfooseja. Futura 1/2007.

- Linturi, Hannu (2017) OPH:n Oppimisen tulevaisuus 2030-barometri. Internetissä https://metodix.fi/2017/01/11/oppimisen-tulevaisuus-2030-blogi-2017/ (https://metodix.fi/2016/12/31/oppimisen-tulevaisuus-2030/) .

- Linturi, Hannu (2020) Delfoin monet tarkoitukset. Metodix https://metodix.fi/2020/03/08/delfoin-tarkoitukset/

- Linturi, Hannu (2020) Delfoi-prosessin vaiheet. Metodix

- Linturi, Hannu (2020) Delfoi-pedagogia. Internetissä https://metodix.fi/2019/11/15/delfoi-pedagogia/.

- Linturi, Hannu (2020) Ilmastot@komo: viisi työkalua ilmastokasvatukseen. Internetissä https://metodix.fi/2019/12/01/ilmastotakomo/ .Rand (2020) Delphi Method https://www.rand.org/topics/delphi-method.html

- Linturi Hannu (2023) Delfoin seitsemän ideaa. Blogisarja https://metodix.fi/2023/10/09/delfoin-seitseman-ideaa/. Metodix Oy.

- Linturi Hannu & Kauppi Antti (2021) Miten tutkimme tulevaisuuksia Delfoi-menetelmällä, Artikkeli teoksessa Delfoilla tulevaisuuteen, toim. Merja Kylmäkoski & Päivi Raino. Humak-ammattikorkeakoulu https://www.humak.fi/julkaisut/delfoilla-tulevaisuuteen/ .

- Linturi Hannu & Kuusi Osmo (2022) Tulevaisuuksia ennakoiva Delfoi-menetelmä. Artikkeli teoksessa Tulevaisuudentutkmus tutuksi. Perusteita ja menetelmiä. (toim. Hanna-Kaisa Aalto, Katariina Heikkilä, Pasi Keski-Pukkila, Maija Mäki, Markus Pöllänen). Turun yliopisto https://www.utupub.fi/handle/10024/153465 .

- Myllylä, Yrjö (2007) Logistic and Social Future of the Murmansk Region until 2020. Joensuun yliopisto, Yhteiskunta- ja aluetieteiden laitos. Joensuu. Verkossa http://joypub.joensuu.fi/publications/dissertations/myllyla_murmanskin/myllyla.pdf.

- Mäkelä, Marileena (2020) The past, present and future of environmental reporting in the Finnish forest industry. Turun yliopiston julkaisua – Annaels Universitatis Turkuensis, Ser. E: Oeconomica. URN:ISBN:978-951-29-8087-1. Verkossa https://www.utupub.fi/handle/10024/149753?show=full .

- Osaamisen ennakointifoorumi: The Finnish National Agency for Education’s Skills Forecasting Forum conducted a multi-phase development project from 2016 to 2019 to explore the future of the workforce and vocational education, employing the Delphi technique as a method to open up futures. Initially, all actors within nine sectoral clusters assessed future developments up to 2035 according to the dynamic multi-level model described by Geels and Schot. From this data, four scenarios were constructed, two of which were selected as the basis for further work. In the second Delphi round, separate Delphi processes were implemented for the nine clusters, which also were based on three levels examining changes in the operating environment, regime adaptation, and signal-level innovation phenomena. See the eDelphi main panel at https://www.edelphi.org/oef and Jukka Vepsäläinen’s video presentation at https://youtu.be/8o2v5nNWqIo?si=T1FyVIibVfX5LdSK.

- Paaso, Aila (2010) Osaava ammatillinen opettaja 2020. Tutkimus ammatillisen opettajan tulevaisuuden työnkuvasta. Rovaniemi: Lapin yliopisto 2010, Acta Universitatis Lapponiensis 174. ISBN 978-952-484-348-5. ISSN 0788-7604.

- Palo, Teea (2014) Business model captured?: variation in the use of business models. University of Oulu, Oulu Business School, Department of Marketing. PDF Full Text http://urn.fi/urn:isbn:9789526203430 .

- Pernaa, Hanna-Kaisa (2020) ”Hyvinvoinnin toivottu tulevaisuus – tarkastelussa kompleksisuus, antisipaatio ja osallisuus”. URN:ISBN:978-952-476-910-5. Osuva http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-476-910-5

- Pihlainen, Vuokko (2020) Asiantuntijoiden käsityksiä johtamisosaamisen nykytilasta ja tulevaisuuden suunnista suomalaisissa sairaaloissa 2030. Experts’ perceptions of the present state of management and leadership competence and future directions in Finnish hospitals by 2030 Kuopio: Itä-Suomen yliopisto, 2020 Publications of the University of Eastern Finland Dissertations in Social Sciences and Business Studies; 223. ISBN: 978-952-61-3377-5 (print), ISBN: 978-952-61-3378-2 (PDF), ISSN: 1798-5757 (PDF). Verkossa https://erepo.uef.fi/bitstream/handle/123456789/22263/urn_isbn_978-952-61-3378-2.pdf

- Rand Corporation: Delphi Method https://www.rand.org/topics/delphi-method.html

- Rubin, Anita (2007) Pehmeä systeemimetodologia. Internetissä https://metodix.fi/2014/05/19/rubin-pehmea-systeemimetodologia/ .

- Rönkä, Anu-Liisa (2019) Kohti vuorovaikutteista riskiviestintää : Tapausesimerkkinä langattoman viestintätekniikan säteily. University of Helsinki, Faculty of Social Sciences. Doctoral Programme in Interdisciplinary Environmental Sciences. Internet https://helda.helsinki.fi/handle/10138/301671 .

- Soini-Salomaa, Kristiina (2013) Käsi- ja taideteollisuusalan ammatillisia tulevaisuudenkuvia. HY. Käyttäytymistieteellinen tiedekunta. Helsinki. Verkossa https://helda.helsinki.fi/handle/10138/41734

- Sunell, Otto (2016) Turvallisuuskulttuuri julkisen hallinnon organisaatiossa vuoteen 2025 tultaessa: Nykytilan kartoitus ja neljä skenaariota. Tampereen teknillinen yliopisto. Tampere. Verkossa https://tutcris.tut.fi/portal/en/publications/turvallisuuskulttuuri-julkisen-hallinnon-organisaatiossa-vuoteen-2025-tultaessa(d16cf10d-2d88-4bcb-8dad-62349f74bf36).html .

- Tamminen, Nina (2021) Mental Health Promotion Competencies in the Health Sector. Faculty of Sport and Health Sciences, University of Jyväskylä. Permanent link to this publication: http://urn.f/URN:ISBN:978-951-39-8666-7 .

- Tapio, Petri (2002) The limits to traffic volume growth : The content and procedure of administrative futures studies on Finnish transport CO2 policy. Internetissä https://helda.helsinki.fi/handle/10138/22446 .

- Tapio, Petri (2002) Disaggregative policy Delphi Using cluster analysis as a tool for systematic scenario formation. Technological Forecasting and Social Change.

- Toivonen, Annette (2022) The emergence of New Space – A grounded theory study of enhancing sustainability in space tourism from the view of Finland. Acta electronica Universitatis Lapponiensis 336. ISBN: 978-952-337-311-2, ISSN 1796-6310. University of Lapland, Rovaniemi 2022. Sähköisen julkaisun pysyvä osoite: https://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-337-311-2 .

- Turoff, Murray (2002) The Delphi Method, Techniques and Applications. Internetissä https://web.njit.edu/~turoff/pubs/delphibook/delphibook.pdf .

- Valtonen, Vesa (2010) Turvallisuustoimijoiden yhteistyö. Maanpuolustuskorkeakoulu, taktiikan laitos. Julkaisusarja 1, Helsinki. Verkossa http://www.doria.fi/handle/10024/74154 .

Kategoriat:Artikkelit, blogi, Tie

Jätä kommentti